Boost vs. Buck Converters: When You Actually Need a Boost-Buck Circuit

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Boost Converters

- Introduction to Buck Converters

- Why Boost or Buck (or Direct Plug-In) Isn’t Always Enough

- Example 1: Charging a 3S Lithium-Ion Battery from a 12V Input

- Example 2: Charging a Battery from Another Battery of the Same Voltage

- Example 3: Building a Portable High-Voltage Power Supply

- Do You Need a Constant-Current Boost Converter?

- Efficiency of a Boost-Buck Circuit

- Is It Worth It?

Boost converters and buck converters are great. They allow you to increase or decrease the voltage. So you can run all kinds of equipment with non-standard power supplies that usually would not be compatible with that. Or you can use them to charge batteries if they are the constant-current variety.

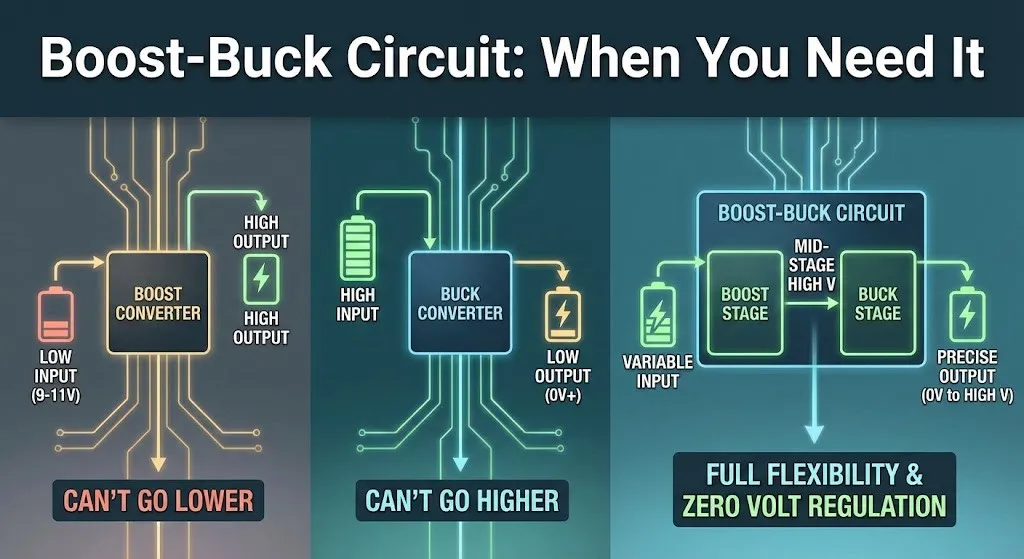

But there are some situations where neither a boost converter, a buck converter, nor plugging it in directly will work. In those situations you need a boost-buck circuit.

Introduction to Boost Converters

Boost converters take a lower voltage input and provide a higher voltage output. They typically have a minimum input voltage of 9 to 11 volts for most boards on the market, with an ideal input of 12 to 24 volts in most cases.

If it's a constant-voltage boost converter, it will have just one knob on it to control the voltage. You don't have any control over the current. It will not limit the current in any way, but the module may turn off boosting past a certain current.

Remember: a boost converter cannot lower the voltage. And the way you control current is by changing the voltage. So if you have a 12-volt input and a 29.4-volt output, if you connect that to a 0-volt load, things will get very hot. Because even though you set the boost converter to one amp, it's not able to lower the voltage enough so that only one amp flows.

But if it's a battery, it can work fine. Because if a 7S battery is nearly dead, it will be at three volts a cell or so. So that's 21 volts. If you have a 12-volt input on the boost converter and you boost to 29.4 volts and you have the current set to one amp, the boost converter can drop its voltage to whatever it needs to be for one amp to flow.

Depending on the battery, that might be 21.5 or 22 volts because the battery is at 21 volts. And that amount of voltage difference is what is required to produce the set one-amp current.

So in this way, when used like this, a constant-current boost converter can regulate down to zero amps, but it can never regulate down to zero volts. Because of that, it cannot regulate down to zero amps over the entire output range. It can only do that within a certain band because of those limits.

Introduction to Buck Converters

A buck converter is basically the opposite of a boost converter. It takes in a higher voltage and outputs a lower voltage. Depending on the buck converter you get, they will have different maximum input voltages. But they all regulate down to zero volts.

There's no buck converter I've ever found, seen, used, or read about that cannot regulate down to zero volts. And because it can regulate down to zero volts, that means it can regulate down to zero amps across its entire range.

There are two versions of this one too. You can have a constant-voltage buck converter and a constant-current buck converter. If it's just a constant-voltage buck converter, then it cannot regulate current at all. It can simply cut off its output when current reaches a set maximum limit.

Buck converters are generally more efficient and they're much safer than boost converters because they can regulate down to zero. So they have full control of the situation.

Why Boost or Buck (or Direct Plug-In) Isn’t Always Enough

You might think that no matter what circuit you're dealing with, you can do one of three things:

- Plug it in directly

- Use a boost converter to increase the voltage

- Use a buck converter to decrease the voltage

And one of those three things will certainly provide a viable solution. Well, that is actually not the case. There are several situations where neither a boost converter nor a buck converter would work, and you do not want to plug them in directly.

Let's look at three examples.

Example 1: Charging a 3S Lithium-Ion Battery from a 12V Input

In the first example, let's say you want to charge a 3S lithium-ion battery—what we call a 12-volt NMC lithium-ion battery. Let's say you want to charge one of those with a 12-volt DC input voltage. How are you going to do that?

Why a Buck Converter Doesn’t Work Here

If you try to do it with a buck converter, you'll end up with a maximum voltage of about 10.5 volts. That's because for each type of converter—whether it's a constant-current boost converter or a constant-voltage boost converter, a constant-current buck converter, or a constant-voltage buck converter—they have an internal voltage drop across them regardless.

It's generally about 1.5 volts. It could be a little lower, closer to 1 volt. It could be a little higher. But a good rule of thumb is 1.5 volts.

So if I have 12 volts going into a buck converter, the maximum voltage I'll be able to get out of it is 10.5 volts. That's just 3.5 volts per cell. So I mean, technically, yes, I could build a 3S NMC lithium-ion battery and charge it up to 10.5 volts, but I'd be missing a lot of capacity. I mean, a lot.

Why a Boost Converter Doesn’t Fully Solve It Either

Now, let's try it with a boost converter. We have 12 volts going in. Same problem: we end up with a 10.5-volt starting voltage, but this is a boost converter. It can increase the voltage, so it's fine, right? We can charge to 4.2 volts per cell by setting the output of the boost converter to 12.6 volts.

The problem is that it can't go any lower. Remember, a boost converter can only increase the voltage. So that means it cannot regulate below 3.5 volts per cell.

So if you've got a battery that is, you know, at around 10.9 volts or something like that, sure, you can connect it to this boost-converter-based 3S battery charger that uses a 12-volt input and it'll work just fine until that battery dies to the point where it is below 3.5 volts per cell.

Let's say it's 3 volts per cell, so 9 volts, and you attach it. Remember, the lowest the boost converter can go to is 10.5 volts. And these converters regulate current by adjusting the voltage. And if the converter is not able to lower the voltage any lower than 10.5 volts, then you'll have a 1.5-volt difference.

And however much current flows is just going to depend on Ohm's law—so the resistance between the input and the output. And you don't want to do that because it could be hundreds of amps. And if you're lucky, some protection mode will kick in and basically you just won't be able to charge a battery that's below 10.5 volts.

The Solution: A Boost-Buck Circuit

So what is the solution? The solution is a boost-buck circuit. The concept is to first boost the voltage to some voltage that's higher than the highest output voltage you want, and then pass that voltage through to a buck converter that lowers the voltage to whatever you want it to be.

Remember, these converters have about a volt and a half of drop or so between the input and the output regardless of the amount of current flowing.

So if we want to charge a 3S NMC battery, we need a max voltage of 12.6 volts. But we know about that 1.5 or so voltage drop. So that means we want to set the boost converter to around 14.1 or maybe even 14.5 volts.

That way we know the buck converter has enough headroom. So let's just do 14.5 and then minus that 1.5. Then we end up with a 13-volt maximum. That gives us plenty of room to regulate down.

And remember, because it's a buck converter, we can regulate down to zero volts. A 3S NMC battery should never be higher than 12.6 volts. So you can regulate down to zero amps because your buck converter will have the ability to regulate down to zero volts.

Example 2: Charging a Battery from Another Battery of the Same Voltage

Okay, let's talk about another example now. Let's say you want to charge a battery with a battery of the same voltage. So let's say we're going to charge a 52-volt battery with a 52-volt battery.

You may be in a situation where you have to do that. You might have two bikes that you take out to some excursion and the more powerful one is the one you want to use. And it's getting low or has already died.

And instead of using the other bike, you can just use the battery from the other bike to charge the bike you want to use. I get that that's kind of an extreme example, but it's totally feasible. And I've talked to people that have been in situations like this.

Also, you might have a 52-volt battery on your bike and it's not practical or feasible to break it down and build a bigger battery. But you have an opportunity where you can add another battery to it, but you don't want to add the batteries in parallel because the battery that's been on your bike is a little old and the new one is brand new.

And it's not good to mix them when their resistances and capacities are so different. So you can put a converter between them to transfer energy.

Example 3: Building a Portable High-Voltage Power Supply

Another example, which is a much more practical one, is making a portable 7S NMC battery-based high-voltage power supply.

You can build a relatively simple 7S battery that has a 29.4-volt max voltage and you can pass that into a boost converter set to 80 volts or so and then pass that to a buck converter that can regulate down to 0 volts.

Now you have this portable power station that you can charge with a 24-volt charger, yet you can output up to 80 volts anywhere on the go. Useful for charging all kinds of higher-voltage batteries and running all kinds of specific equipment.

Do You Need a Constant-Current Boost Converter?

A note about this: if you're interested in making a boost-buck circuit, you do not have to have a constant-current boost converter. It can be a constant-voltage boost converter because remember, current is regulated by regulating the voltage, and you're doing that with the buck converter because it can regulate voltage all the way down to zero.

So you don't have to regulate current with the boost converter. All you have to do is regulate voltage. So that means you can buy a boost converter that doesn't have a current control knob and it will work fine.

If you have one that does have a current control knob—meaning it is a constant-current boost converter—you can still use it in a boost-buck circuit. You just have to set the current to maximum.

When you set the current to maximum on either a constant-current boost converter or a constant-current buck converter, you're essentially putting it in constant-voltage mode. It doesn't mean that it will supply the max amount of current. It just means it will allow up to the maximum amount of current to be supplied without lowering the voltage to regulate that current. It will just keep the voltage steady.

And that's what you want for the first stage of a boost-buck circuit.

Efficiency of a Boost-Buck Circuit

So let's talk about efficiency. These converter boards, in reasonable, realistic, but still ideal conditions, get about 95% efficiency. So if you multiply 95% times 95%, you'll end up with 90.25%.

That's not too bad. That means for every 100 watts you put into the boost-buck circuit, you get just over 90 watts out, with 10 watts of heat just dissipated between the two.

They're not evenly split because the devices will have different resistances and other factors, but we can generally just cut that in half and say each converter will be dissipating five watts of heat, which is nothing for any reasonable-size converter that has a tiny fan on it.

In severe situations where you're pulling hundreds of watts through both of these converters in series, efficiency might drop to something like 90% per converter, which comes out to 81% after you multiply them.

And while that might seem pretty low, pretty much all of the state-of-the-art battery cells, motors, and everything else advertise their peak figures in terms of watts and current that draw the system down to the low 80s in percentages of efficiency.

So, you know, just like those things, most of the time this will be so efficient it will not even matter.

Is It Worth It?

So is it worth it? Absolutely it's worth it to use a boost-buck converter circuit, because it enables you to do things that you literally cannot do without them.

And that is worth paying the slight added cost from the lost efficiency, because that's just the price you pay to be able to do these kinds of things.

We hope this article helped you understand the concept of the boost-buck circuit and how it is not only beneficial, but sometimes required. Thanks for reading.