How to Test Lithium Ion Battery Cells and Packs With a Constant Current Buck Converter

Table of Contents

- Two obvious ways to test with a constant current buck converter

- Limitations of using the buck converter on the input

- Using the buck converter on the output to charge a cell

- A third way: put the cell in series with the buck converter output

- How the regulation works in a series setup

- Major drawback: you can discharge past zero and reverse charge the cell

- Example: 10 amps discharge with the buck converter adding voltage

- Safety: monitor cell voltage and temperature independently

- Simple charts

- Calculating resistance from a voltage drop under 10 amps

- Conclusion

Did you know you can use a constant current buck converter to test battery cells and battery packs? There are purpose-built active loads and battery testers that you can buy but they are expensive and they only do one thing. If you know how to test a battery with a constant current buck converter then you can use that same constant current buck converter to power lights or a fan or even charge another battery.

Two obvious ways to test with a constant current buck converter

Now there are two obvious ways that you can use a constant current buck converter to test a power supply or battery. You can put it on the input and then you can power some dummy load or you can put it on the output and charge it and see how it responds to a charge current. While both of those things are interesting and can provide some useful information there are some inherent limitations with both concepts.

Limitations of using the buck converter on the input

For one most buck converters have a minimum input voltage of 9 or 10 volts. Any buck converter that can work at a very low voltage such as a single lithium-ion cell it's going to have a very very low current capability and it won't be useful for testing. So for all practical purposes for any buck converter that would have enough current carrying capacity to use for testing it would not have support the input voltage range required to put a single cell on the input.

Using the buck converter on the output to charge a cell

You can put the single cell on the output by charging the cell and seeing how it responds to a charge current that can be helpful. For example if your cell is at 3 volts and you have the constant current buck converter set to 1 amp and a max voltage of 4.2 volts and if you turn it on and the voltage springs up to like 3.9 or 4.1 volts right away then you know it's a bad cell you know it has a very very high resistance.

So you can use a constant current buck converter with a cell attached to the output to investigate the health of the cell to a degree but you won't be able to get the discharge resistance and you won't be able to know exactly how it will behave in the real world because while charging and discharging is similar it's not just completely backwards. It is a complex chemical reaction that works one way in one direction and one way in the other direction. So while you can investigate some parameters of cell health you can't really get the true equivalent series resistance doing it that way.

A third way: put the cell in series with the buck converter output

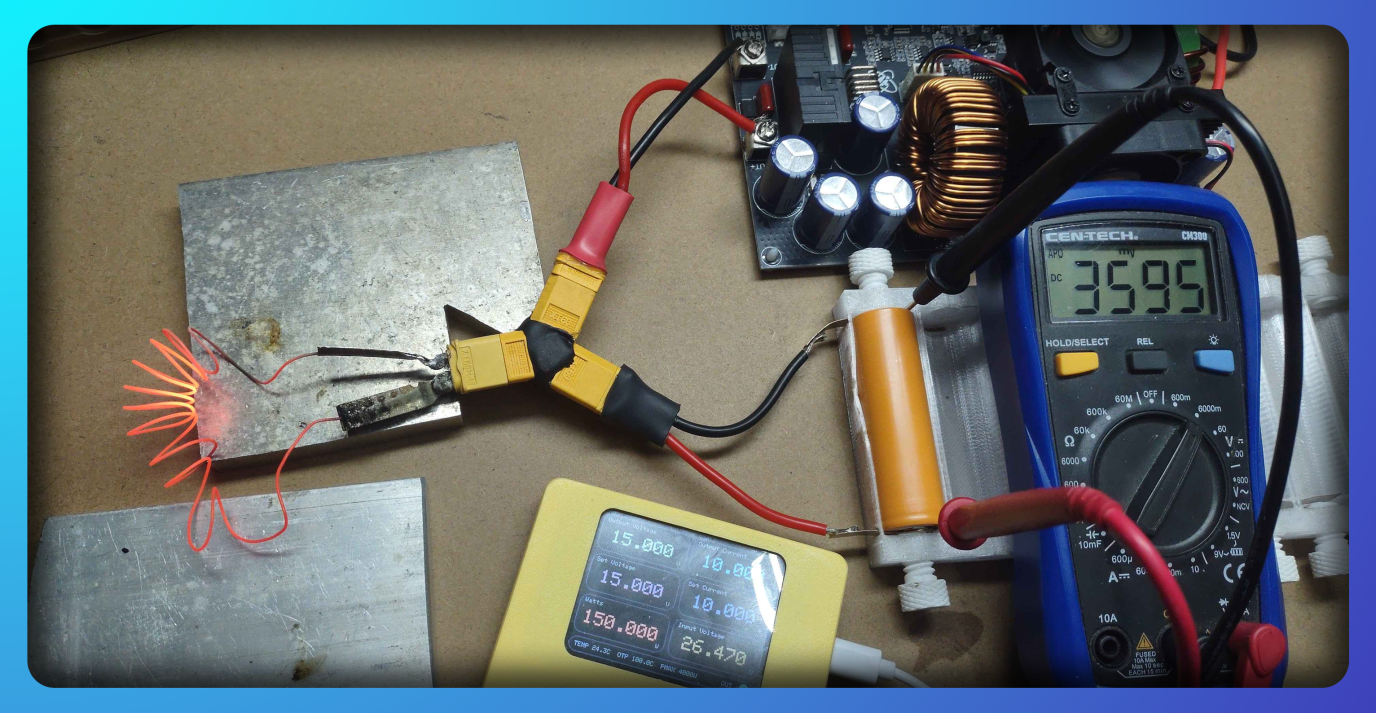

So that brings us to a third way to use a constant current buck converter to test a cell. You put it on the output but instead of putting the cell parallel with the output which is the traditional way of connecting it you put it in series with the output. So you set the buck converter to say 1 amp and 20 volts just give it a nice chunk of headroom and then you put it in series with a 4.2 volt cell or 3.7 volt cell whatever the cell is charged to and then you connect it to a dummy load.

How the regulation works in a series setup

Now how a buck converter regulates current is it changes the voltage to whatever it needs to be to maintain the set amount of current. So when you're charging a battery cell if you have it set to 2 amps and the battery cells at 3 volts then the buck converter will go to whatever voltage above 3 volts is required for 2 amps of current to flow. But that's because the cell has its own voltage. It's a battery after all. But if you connect it to a dummy load which is basically a zero volt cell there's a large voltage difference so the buck converter has to drop to a very low value to maintain 2 amps.

So when you hook it up in series like this you'll have some minimum current when it's on because you won't be able to turn off or regulate the cell directly but because it's in a series circuit with the buck converter that can adjust its voltage what you end up with is the current setting on the buck converter regulating the voltage required on the line for it to maintain the amount of current that you set. And as the cell dies the buck converter has to automatically increase its voltage to maintain the amount of current you set.

Major drawback: you can discharge past zero and reverse charge the cell

So the one big drawback of this is that you can run the cell down to not only zero but even pass zero and start reverse charging the cell which is very dangerous. So you have to independently monitor the cell voltage when it's set up like this.

Example: 10 amps discharge with the buck converter adding voltage

So for example you start with a dummy load a 4.2 volt cell and the buck converter set to 10 amps. You turn it on the buck converter might be outputting 4 volts or and we know the cells at 4.2 volts so that's 8 volts total and we have 10 amps flowing in the dummy load in this example. As the cell voltage drops to 3.9, 3.8, 3.6 and so on and you see the buck converter increase its voltage from 4 volts to 4.1, 4.2 and so on to maintain whatever the total voltage was initially that was required for 10 amps to flow because the resistance hasn't changed. As the cell depletes its resistance will increase. Once the cell gets to around 3.4 volts its resistance will plummet at which point the buck converter will have to have to add more and more voltage to the circuit to maintain the set amount of current.

Safety: monitor cell voltage and temperature independently

This is totally safe as long as you monitor the temperature of the cell and the voltage of the cell independently of whatever the voltage of the buck converter is. Make sure the cell doesn't go below 2.8 volts or so and make sure it doesn't get any hotter than 70 degrees Celsius or whatever it says in the data sheet. You will be totally fine. Once it reaches the cutoff point simply press the button on the buck converter to turn it off and you are good to go.

Simple charts

Below are simple charts you can include in the article. These are basic HTML charts using tables so they can be used anywhere without scripts. They are based on the example narrative above.

Chart 1: Example trend as the cell voltage drops and the buck voltage rises

Cell voltage volts | Buck voltage volts | Total volts | Current amps

4.2 | 4.0 | 8.2 | ~10

3.9 | 4.1 | 8.0 | ~10

3.6 | 4.2 | 7.8 | ~10

3.4 | 4.5 | 7.9 | ~10

3.2 | 4.8 | 8.0 | 10

Chart 2: Suggested cutoff and temperature checks

Parameter | Suggested limit from the text | What to do

Cell voltage volts | Do not go below 2.8 | Turn off the buck converter at cutoff

Cell temperature degrees Celsius | Do not exceed 70 or datasheet limit | Stop the test if it overheats

Calculating resistance from a voltage drop under 10 amps

At any point during the test during the main portion of the test not in the beginning or the end where the resistance is highest You can turn it off and turn it back on again and take note of how much the voltage drops when you turn on the current. Then you can do the math to determine the resistance of the cell.

Resistance example using the 10 amps scenario

Using the example above, say the cell is resting at 3.80 volts with the load off. You turn the buck converter on at 10 amps and you observe the cell voltage drops to 3.60 volts under load. The voltage drop is 0.20 volts at 10 amps.

Resistance equals voltage drop divided by current.

Voltage drop volts equals 3.80 minus 3.60 equals 0.20

Current amps equals 10

Resistance ohms equals 0.20 divided by 10 equals 0.02 ohms

That is 20 milliohms.

Conclusion

We hope this article helped you learn everything you needed to know about how to test a lithium-ion battery cell with a constant current buck converter. Thanks for reading.