The Effects of Resistance And On A Battery

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Series and Parallel Resistance

- Scope of This Article

- Understanding Resistance

- Battery Example: 20S5P Using Molicel P42A Cells

- Data Collection and Observation

- Calculating Resistance with Ohm's Law

- Test Data and Projection

- Expected vs. Actual Power Output

- Understanding Power Loss and Non-Linearity

- Effect of Added Resistance on Performance

- Comparison with a Theoretical Perfect Battery

- High-Current Behavior and Non-Linearity

- Interpreting the Power Curve

- Summary of Resistance Effects

- Does Putting Nickel Between The Cells And Copper Hurt Performance?

- Additional Benefits of the Copper Nickel Sandwich

- Calculating Nickel's Contribution to Resistance

- Detailed Calculation of Nickel Resistance

- Comparing Calculated Resistances

- Visual Comparison of Battery Performance

- Wrapping It Up

Introduction

Today, we need to talk about series conductors and resistance. When you're building a battery, you generally have to use several sets of series connectors. That's because most batteries have to have several cell groups in series in order to reach the desired voltage.

Series and Parallel Resistance

The problem with putting cell groups in series is that the resistance of the series conductor that you use is added to the battery. It's not just added once. It's added several times. If you have a 10 megaohm resistor and you put it in series with another 10 megaohm resistor, then you've got 20 megaohms of resistance. If you put two 10 megaohm resistors in parallel, you have 5 megaohms of resistance. That's how that works.

So the more series connections you have, the more amplified the resistance of your series connection is going to be. This is why it's important for high current batteries to use copper as the main conductor for series connections in battery packs.

Scope of This Article

Which brings me to the topic of this article. There is a lot of confusion out there related to what metals to use for a battery pack, which ones are the best, how to attach them, what you should and shouldn't do. And we already have an article for which metal to use when building a battery pack. This is not an article about copper versus nickel. This is also not an article about putting battery cells in series for increased voltage. We have another article based on that. You should check both of those out. This article is specifically about the effects of resistance on a battery related to series conductors and the materials used. This article is about what does and doesn't appreciably affect performance when it comes to a lithium ion battery and its series conductors and how they are welded or attached.

Understanding Resistance

The first thing we need to cover is really what is resistance and how does it affect an electronic circuit? What does it mean related to the voltage and the current? So what is resistance? Resistance is literally just that. It's a given material's resistance to the flow of current. The thing about resistance, though, is it doesn't just affect things in a consistent way. How much the resistance affects something depends on how much current is running through it.

What that means is if you're not running a lot of current, you can get away with having very high resistance connections, poor solder joints, loose welds, all kinds of things, and you'll never even notice a problem. That's because all of those poor connections, they create high resistance points that cause larger than normal amounts of voltage drop, but that's all happening per amp. That's very important for you to understand. The effects given by resistance happen per amp. So if the resistance you have in your battery or circuit is causing the voltage to drop by 1 volt under a 2 amp load, then that means it's going to drop half a volt per amp. And that's going to be pretty darn consistent all the way up.

Yes, it's technically true that as most things get warmer, their resistance increases. But honestly, it takes a lot of temperature to cause enough of a change in resistance for it to have any appreciable effect on the situation. It has to be so hot that you wouldn't want to run it that hot. Also, in lithium ion batteries and several other types of batteries, the resistance changes throughout the state of charge. But it pretty much stays the same throughout the entire state of charge, and it's a little higher towards the higher end of the voltage, and it's a lot higher towards the lower end of the voltage range. So in those isolated ways, the resistance can change. But in the scope of things and at any scale where it matters, you can rely on the voltage drop caused by resistance to be A, linear, and B, directly linked to current.

Battery Example: 20S5P Using Molicel P42A Cells

So let's talk about a battery that I just recently built for a good friend of mine. It's a 20S5P using Molicel P42A cells. So 20S means that it is 20 cell groups in series. 5P means that each one of those cell groups has five cells. Molicel P42A typically have an internal series resistance of about 15 milliohms. Considering the fact that this battery has five of those cells in each cell group and those cells are in parallel, remember, the resistance is divided.

If you've got equal resistance things in parallel, you divide the resistance of one thing by the total number of things to find the actual resistance of the group. In this case, 15 divided by 5 is 3. So that means each one of these cell groups have 3 milliohms of resistance. But remember, it's 20 of those cell groups in series. So 3 times 20 is 60. That means the resistance of the battery as measured above 60, any difference is going to be the resistance of everything but the cells. So that means the series connections, the wires, the welds, the solder joints, the connectors, everything else.

Data Collection and Observation

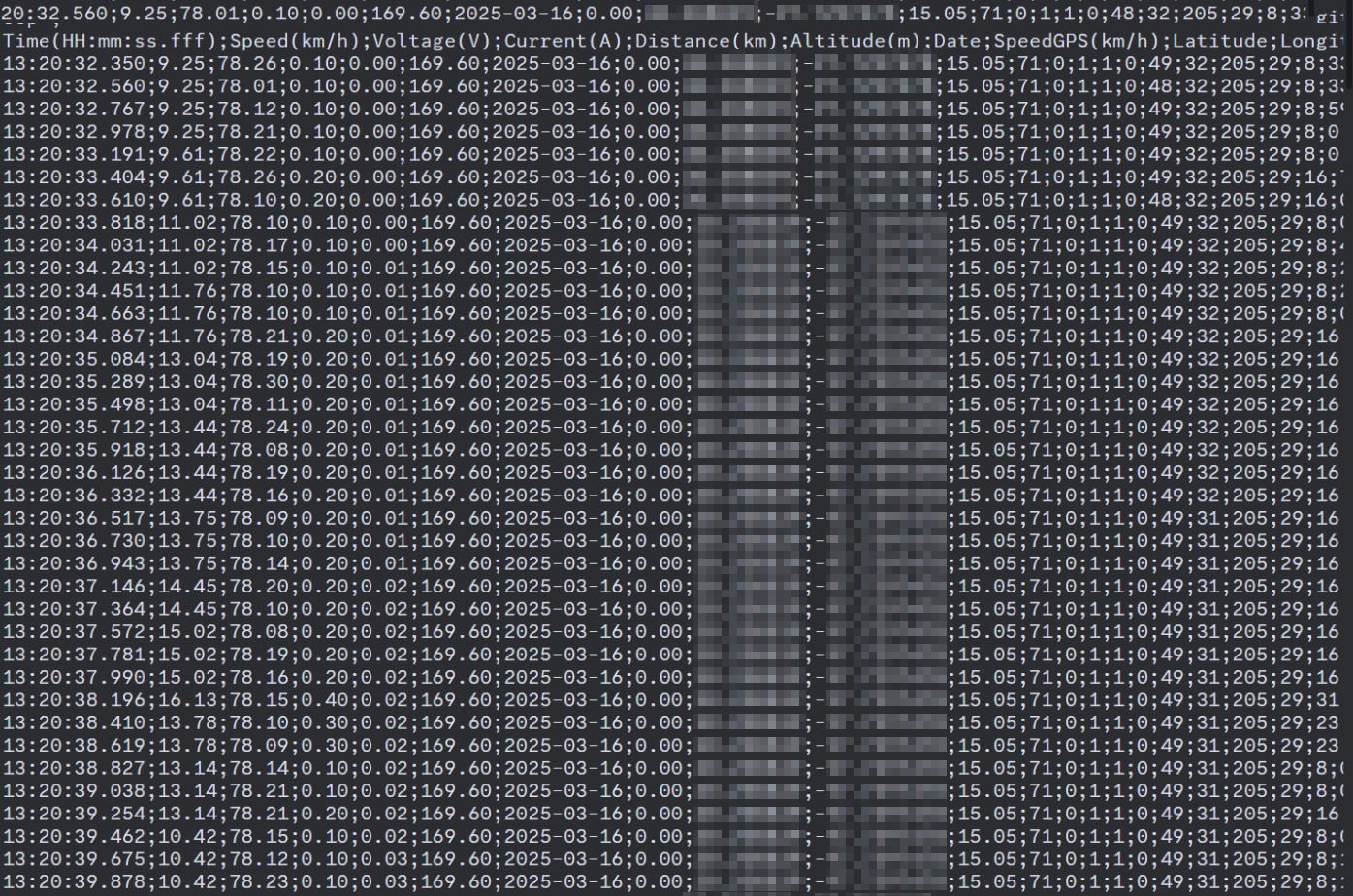

So my friend has a pretty nice bike and one of those really snazzy Egg Rider displays that does logging and all of that. So after he got the battery, he took it on a few rides and he sent me the data. The data itself is nothing good to look at. It's just a massive block of numbers. It does tell you what the numbers mean.

Calculating Resistance with Ohm's Law

In the chart, you can see his voltage is about 78 volts, just above 78 volts initially. And then the voltage falls proportionally as current goes up. This effect that resistance has on the voltage will allow us to work backwards and determine what that resistance was because we know what the voltage was and we know what the current was. So we can find out what the resistance is using Ohm's law. So how do we do it? Well, it's really easy.

All we have to do is take the starting voltage of 77.99 and subtract the loaded voltage of 74.29, and we're left with 3.7 volts, which coincidentally just happens to be the nominal voltage of an NMC lithium ion cell. And then we take the loaded current of 48.9 and subtract the essentially unloaded current from it.

The reason we do this is because we didn't start with no current. So we can't consider our voltage clean until we remove that current from it. And this is how we do that mathematically. And we're left with 48.4 amps. So here's the big, super long, complicated equation. 3.7 volts divided by 48.4 amps equals 0.764 ohms, or 76.4 milliohms. We know that must be the internal resistance of this battery because it would require some other internal resistance of this battery to produce the same result. And I can explain that in this next chart.

Test Data and Projection

Here, we're using real world test data that was acquired out on a bike ride, and we're plugging that into a chart to not estimate but calculate what the effects of the resistance of the battery would be at varying currents. So we did the test at about 50 amps, and we got a reading.

Expected vs. Actual Power Output

What this chart basically is is the output of that equation, but instead of with 50 amps going in, it's 0 to 100 amps and everything in between. Let's check out the first chart, the actual power delivered. See that dotted gray line? That's what most people expect their power to be. When they learn that watts is volts times amps, that's what they do. If they have an 80 volt battery and they're running 50 amps, they say that's 4,000 watts.

Well, it's not really 4,000 watts because there are power losses due to resistance. And because we know the resistance of this battery, we can project its power loss over a range. Now, notice that the expected power is linear because watts is current times volts. That's a linear relationship. But the actual power is non-linear because the power loss is being subtracted from it. But it's mostly linear because we're running this battery within its limits, and I'll explain that shortly.

Understanding Power Loss and Non-Linearity

Let's go to the power loss chart. You can see the power loss chart is very non-linear. This is because of a tricky thing that happens inside a circuit. When calculating power loss in a resistor, the current ends up being squared because of how voltage, current, and resistance are related.

The basic formula for power, of course, is power equals volts times current. That tells you how much energy is being delivered. Ohm's law states that voltage equals current times resistance, though. So when you substitute the voltage in the power equation, you end up replacing the V with the formula.

So if power equals I times R times I, that's equal to I squared times R. So even though power is voltage times current, when you're calculating power loss in a resistor, it's voltage times current times current. So now you may start to realize that resistance is very important because even though voltage drop caused by resistance will always be linear and proportional to the current, the power loss, lost as a result of that resistance, is non-linear. And its effects become more and more pronounced as resistance increases.

Effect of Added Resistance on Performance

So as an experiment, let's add a very, very small amount of resistance to this entire battery. Not to each series connection, but to the entire battery. We'll add about 50 milliohms, and it'll bring us to 125 milliohm battery. Now look at this chart. At the same voltage and over the same current range, we see a lot lower performance.

The first battery with 76 milliohms of resistance or so only saw 200 watts of power loss at a 50 amp load. The second battery sees 250 watts of power loss at 50 amps. That's 25% more. Check out the voltage drop. The first battery drops just under eight volts at a 100 amp load. The second battery drops over 12 volts at the same 100 amp load. The first battery stays above 90% efficiency all the way to a 100 amps. The second battery drops well below 85% efficiency at a 100 amps.

Comparison with a Theoretical Perfect Battery

So now let's look at this chart. This chart shows a perfect battery that has the resistance of just the Molicell P42As in their configuration. Meaning no conductor resistance, no wire resistance, no connector resistance, nothing is accounted for. This is as good as the battery could possibly be, and it could never be this good because you gotta connect the cells somehow, right? That's the purple line.

That would be a perfect battery. The actual battery is very, very close. You can see that. It doesn't deviate from it much at all at these scales, but I'll get to that in just a moment. But you can see even at this scale, the orange line does deviate quite a bit. You can see it's really starting to bow out there.

High-Current Behavior and Non-Linearity

If you look at the actual power delivered chart, you can tell that the battery can handle a particular load if the current you want to run is within the most linear portion of the curve. Because we projected the current out to 500 amps, we can really see what's going on here.

Even the perfect battery gets very nonlinear. The actual battery is looking pretty rough, and the 125 milliohm battery is in a very, very, very bad situation. You can see at a certain point, because of resistance, as you draw more current from the battery, you actually get less power output. The thing is, the maximum power for any battery, you're gonna reach that far before you get to this point, but it's still really interesting and very thought-provoking and very informative to see this on this chart this way.

Interpreting the Power Curve

So let's look at this orange line. Once we get to about 320, maybe 315 amps, the resistance is so much that any further current will add so much additional power loss that that power loss will be more than the power gained. But you can clearly see that's not happening at lower currents.

You can see that the actual battery, the turquoise line, will perform very well from zero to 100 amps. It will perform barely any worse than an impossible battery that has zero resistance series conductors. That's because this battery was built for 100 amps. Actually, it was built for a 50-amp load, but it's good to overbuild, so it's built for 100 amps. This battery's never gonna break a sweat under its intended operation. So as long as it's run within those limits, you can call that a great battery. But check out 300 amps. That's not such a great battery at 300 amps, is it? We know it's not such a great battery at 300 amps because the curve of the line is very nonlinear at that point and it deviates a lot from the perfect battery.

Summary of Resistance Effects

So this clearly demonstrates a couple things. Number one, it shows resistance's effect on a power supply. It shows how resistance will cause the actual power you get to be lower than your expected power, and it also shows that a lot of heat and wasted energy can build up inside your device as a result of the resistance. But it also shows that at certain levels of current, certain resistances just don't matter. You can have a very high resistance if you're running a certain load. The math is kind of complicated. Charts and graphs and programs surely help, but you do have the ability to understand the situation and you can determine what will and won't cause a problem in a battery.

Does Putting Nickel Between The Cells And Copper Hurt Performance?

So now that we understand the math, let's dispel a myth that is widely circulated among the battery building community. It is widely believed that placing nickel between the battery cells and the copper series conductor causes a drop in performance. This is incorrect. Let me explain.

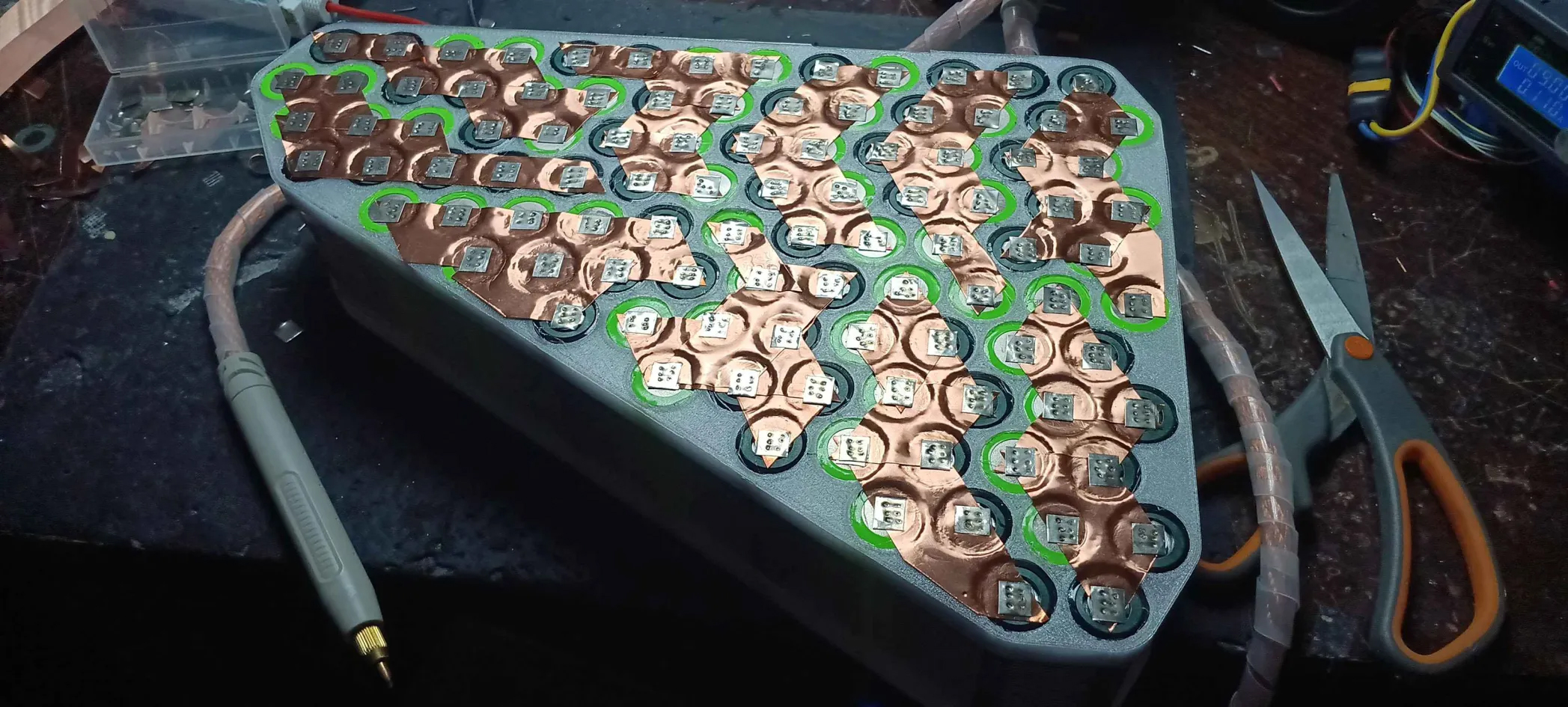

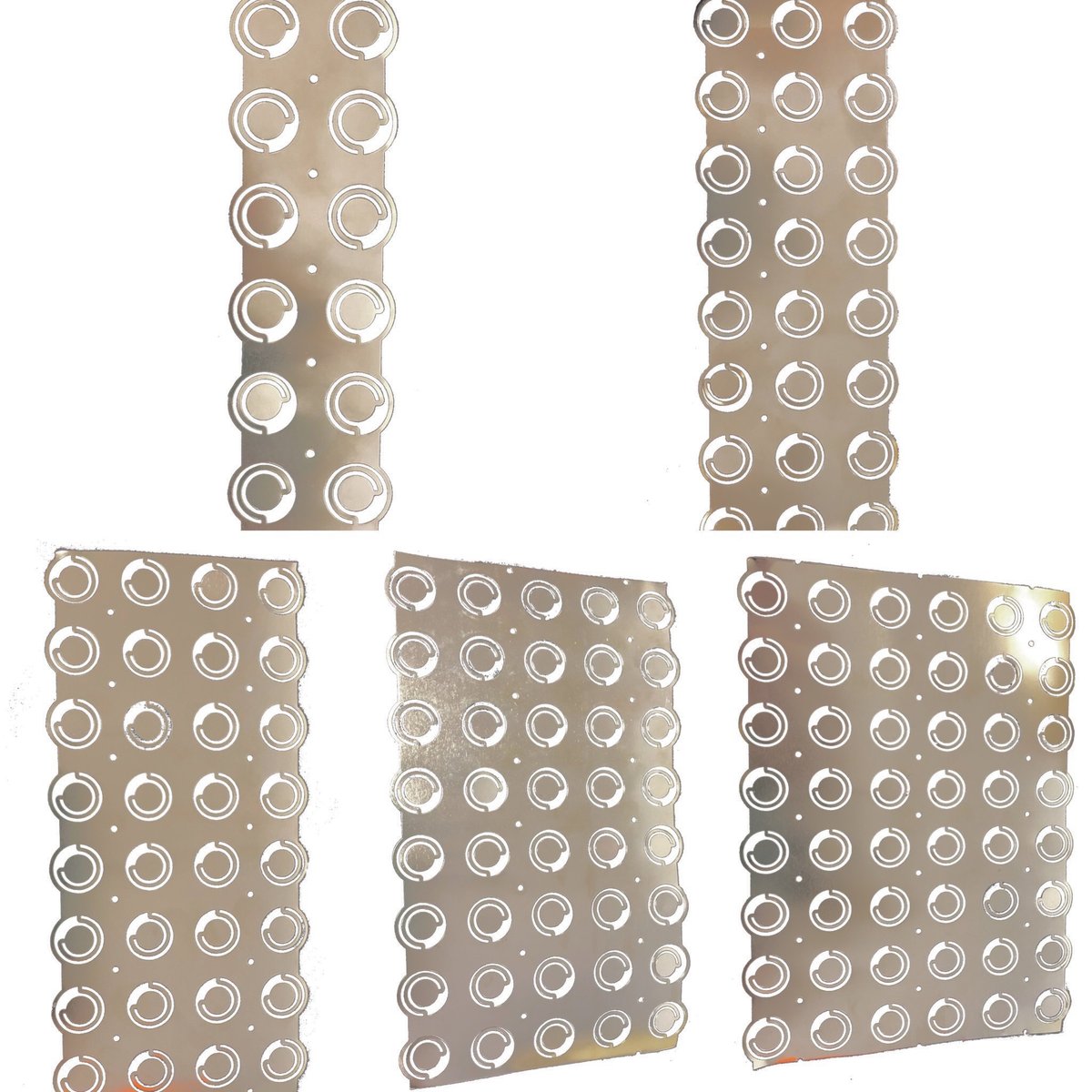

There's a method of building a battery called a copper nickel sandwich. We've written an article about that. You should really go check that out. There's all kinds of ways of doing a copper nickel sandwich, and one of those ways involves actually making a sandwich where you have nickel bread and copper meat. So it's cells and then nickel, copper, nickel. People like to do this sometimes for a variety of reasons. You could be building a battery and then change your mind and wanna cover it with copper.

That's happened. You could have a low power welder. Doing that makes it easier to weld. That's because low power welders can weld nickel just fine, but they really struggle welding copper so you're not gonna get a really good connection through the cell. But if you do a normal nickel build and then weld copper on top of it, if those welds on top aren't super perfect, it's really okay, because you're only reinforcing the nickel on top. If they are perfect, then there's absolutely no problem with doing it that way.

Additional Benefits of the Copper Nickel Sandwich

I'm just saying that if your welds aren't perfect, doing it that way allows you to add copper to a battery and get almost all of the benefits from it without having a high power welder. If you do have a high power welder, you may wanna do this for other reasons. Nickel adds rigidity to a battery.

So the more nickel you put in a battery, the stronger it's gonna be along that axis. Number two, any conductor you add in parallel to any other conductor will lower the resistance of it. I'll repeat that again. When you add a resistor to another resistor in parallel, the resulting resistance is always lower than the individual resistance of either one of those things. So that means if you have a sheet of copper, even though nickel is four point something times the amount of resistance as copper, if you add a sheet of nickel to that sheet of copper, you are not increasing the resistance. You are decreasing the resistance of that conductor.

Calculating Nickel's Contribution to Resistance

It is very popular to be under the assumption that any nickel placed between the copper and the cells will cause some sort of noticeable performance loss. This is absolutely false. We can calculate the resistance of a piece of nickel sitting on top of a cell because from the perspective of the current, the only nickel that the current is gonna go through is just the square of nickel that's just above the cell.

We can say that this block of nickel is 0.15 millimeters tall and eight millimeters wide and eight millimeters long. The path of the current is flowing through the thin axis, the 0.15 millimeter axis. So we can calculate the resistance that the current will experience coming out of the cell and going into the series conductor, which at this point is a nickel copper composite, but it has to go through the nickel first. That will add some resistance.

Detailed Calculation of Nickel Resistance

So let's see how much it's gonna add. The resistance can be calculated by the formula R equals rho times L divided by A. First, the thickness, which is L, of 0.15 millimeters is converted to meters. So we got 0.00015 meters. And the cross-sectional area, which is A, is calculated as eight times eight, which comes out to 0.000064 meters squared. Then, using nickel's resistivity of approximately seven times 10 to the negative eight ohms, we can compute the resistance by multiplying the resistivity by the thickness and dividing by the area. And this process yields a resistance of 0.000164 meters.

Comparing Calculated Resistances

So let's take the actual battery resistance of 76.4 milliohms, and let's subtract the cell resistance of 60 milliohms, and we're left with 16.4 milliohms of difference. We can set that 16.4 off to the side for now, and we'll just work with the 60. And let's go backwards. It's 20 cell groups in series, so that's 60 divided by 20 gives us three milliohms, and it is five cells in parallel, so that's three times five for 15 milliohms, and we have to add 0.000164 to each cell. So instead of a 15 milliohms cell, we're gonna effectively have a 15.000164 milliohms cell.

Well, we've got five of those in parallel, so we divide that by five, and we get 3.0000328 milliohms. And then we have 20 of those groups in series, so we multiply that by 20, and we get 60.000656 milliohms. And then we add our other resistance caused by the wires, connectors, et cetera, which was 16.4 to that, which gives us 76.400656 milliohms. Remember, our original resistance was 76.4, and after adding the nickel to each cell, we have a total resistance of 76.400656 milliohms. Absolutely nothing.

Visual Comparison of Battery Performance

Let's go ahead and plot it against the real battery. The dotted line is the actual battery, and the solid line is the battery with the extra nickel between the copper and the cell.

Wrapping It Up

Understanding how series conductors add cumulative resistance—and how that resistance, in turn, affects voltage and power output—is fundamental to building efficient battery packs. Our exploration shows that even small resistive losses in connectors, wires, or welds can be amplified when multiple cell groups are linked in series. However, through careful material selection—using low-resistivity copper and even incorporating a thin nickel layer when needed—we can largely negate these losses. The detailed analysis and real-world data underscore that with proper design and precise calculations, battery performance can closely approach theoretical ideals, ensuring reliability and efficiency under intended load conditions.